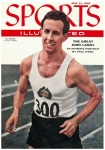

A Man Conquers Himself

Gentle John Landy, after one of history's fastest Mile times, could feel only sadness and defeat. Here is the story of an amazing, dedicated athlete—and an amazing human being: "I'd rather lose a 3:58 Mile than win one in 4:10."

By Paul O'Neil, Sports Illustrated

The townspeople of Fresno, California, Raisin Capital of the World and Pearl of the San Joaquin Valley, share one obsession: they are track & field fans. Kids in Fresno can recite the latest clockings in the 100 and 220 yard dash the way kids in Brooklyn recite baseball averages, and their elders—waitresses, ranchers, truck drivers and bankers—recall the feats of the great men of running with a pride and awe which is probably unique in the U.S. Last Saturday evening 16,000 of them—as many as could possibly jam past the gates of Fresno State College's little Ratcliffe Stadium and into its seats, its infield and the grassy areas around the ends of its famed, sand-colored clay track—were present there and garrulous with anticipation.

At 7:14 o'clock, give or take a few seconds, every man, woman and child of them were on their feet and emitting a pleading roar which must have been heard on the distant Sierras, for around the far turn at Fresno came Australia's John Landy, one of the loveliest runners ever born, floating like blown tumbleweed toward a new world record in the Mile run. The air was chilly, although the declining sunlight still slanted brightly on the green grass and the motley of 1,400 athletes—now spectators almost to a man—who had gathered for the 30th running of the West Coast Relays. A plaguing wind was blowing down the backstretch in gusts up to seven miles an hour. But Landy, whose warm smile and shock of curly brown hair had become familiar to millions of newspaper readers and televiewers during the two weeks of his U.S. tour, had built the foundations of a historic race.

He had been boxed momentarily on the first turn between ex-Occidental College Miler Jim Terrill and former Yaleman Mike Stanley. But he had slid clear at 200 yards, with Villanova's young Dublin Irishman, Ron Delany, at his heels, and from then on, running like some tanned Inca courier, he had steadily left the field behind. He had hit the quarter miles with almost absolute precision—59.9, 2:00.1, 3:00.8. Then, fiercely bent on penance for his one-yard defeat at the hands of his fellow Australian, Jim Bailey, seven days before, he fled into the final lap with 57 seconds to go to break his Mile world record.

How was he doing? It was impossible to say. But the crowd, remembering that he had run 57.2 in the final quarter against Bailey in the Los Angeles Coliseum, urged him on with a steady, deafening torrent of sound. He was 35 yards ahead of Delany in the backstretch, 40 yards ahead as he lengthened his stride in the turn, and 50 yards ahead and running all alone as he came rolling down the stretch. He went through the tape with his style unflawed by weariness, and turned back, strolling casually, to find out the news. The time was 3:59.1—his sixth sub-4 minute Mile, and his second in one week. He had missed.

He walked immediately toward an Australian radio man, waiting near the turn with a microphone. As he did so, his chest rose and fell laboriously beneath the green jersey of the Geelong Guild Athletic Club. But he took one last deep breath and then spoke almost as normally as if he had simply hiked the mile. He was bitterly disappointed. "It just wasn't there to give," he cried. "I had no sparkle in me at all. It was ridiculous not to have run 3:56. A near-record breaker—perhaps that's my fate. I'm disappointed. I know in my heart I can run better than that. It was just another run—a time trial—just another performance."

A little later, back in the red brick dressing room, surrounded by reporters he went on: "It may be that I've had too many hard races this year. In both cases here I doubt that I was running as well as in Australia, although I felt better tonight than last week. I was not exhausted at the end. I had the energy but I was just not getting it out. I was very strong." Had competition aided him in the race against Bailey in Los Angeles? "The competition," he said with a wry grin, "didn't present itself until it was too late to be of any use." He continued: "This may have been my last Mile. I'll be running 1500 meters before the Olympics, and I had hoped to give you a new record."

Thus ended one of the most astonishing and admirable adventures in the history of athletics in the U.S. And one, in the minds of those who listened to him in Fresno, which was only dramatized by John Landy's unfeigned disappointment. In a single fortnight he had flown 9,000 miles from Australia to the U.S., had not only accepted a burden of press conferences, newsreel performances, radio shows and television spots which would have staggered a candidate for the U.S. Senate, but had won his auditors to a man with his poise, his patience and an articulate honesty.

In accepting, without reserve, the responsibility of serving as an "ambassador" for Australia and a sort of salesman for the Melbourne Olympics, he had virtually promised to run two four-minute miles in eight days. And, for all the nervous strain of his incessant extracurricular activities, he had done so—a feat without precedent in the annals of track. If he had been beaten by a jump in the surprising race with Jim Bailey he had also made the pace and thus opened the door of fame to his fellow countryman.

Continue reading at: si.com/vault