Pre & Me

I told myself there was much to be learned from such a display of passion, whether you were running a Mile or a company.

By Phil Knight, for Runner's World

Excerpted from Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of Nike, by Phil Knight. Copyright © 2016 by Phil Knight. Reprinted by permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

* * *

In 1972, we turned our attention to the Olympic Track & Field Trials, which that year were being held, for the first time ever, in our backyard: Eugene, Oregon. We needed to own those Trials, so we sent an advance team down to give shoes to any competitor willing to take them, and we set up a staging area in our store, which was now being ably run by Geoff Hollister. As the Trials opened we descended on Eugene and set up a silk-screen machine in the back of the store. We cranked out scores of Nike T-shirts, which Penny [Knight’s wife] handed out like Halloween candy.

With all that work, how could we not break through? And, indeed, Dave Davis, a shot-putter from USC, dropped by the store the first day to complain that he wasn’t getting free stuff from either adidas or Puma, so he’d gladly take our shoes and wear them. And then he finished fourth. Hooray! Better yet, he didn’t just wear our shoes, he waltzed around in one of Penny’s T-shirts, his name stenciled on the back. (The trouble was, Dave wasn’t the ideal model. He had a bit of a gut. And our T-shirts weren’t big enough. Which accentuated his gut. We made a note. Buy smaller athletes, or make bigger shirts.)

We also had a couple of semifinalists wear our spikes, including an employee, Jim Gorman, who competed in the 1500. I told Gorman he was taking corporate loyalty too far. Our spikes weren’t that great. But he insisted that he was in “all the way.” And then in the marathon we had Nike-shod runners finish fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh. None made the team, but still. Not too shabby.

The main event of the Trials, of course, would come on the final day, a duel between Steve Prefontaine and the great Olympian George Young. By then Prefontaine was universally known as Pre, and he was far more than a phenom; he was an outright superstar. He was the biggest thing to hit the world of American track & field since Jesse Owens. Sportswriters frequently compared him to James Dean and Mick Jagger, and Runner’s World said the most apt comparison might be Muhammad Ali. He was that kind of swaggery, transformative figure.

To my thinking, however, these and all other comparisons fell short. Pre was unlike any athlete this country had ever seen, though it was hard to say exactly why. I’d spent a lot of time studying him, admiring him, puzzling about his appeal. I’d asked myself, time and again, what it was about Pre that triggered such visceral responses from so many people, including myself. I never did come up with a totally satisfactory answer.

It was more than his talent—there were other talented runners. And it was more than his swagger—there were plenty of swaggering runners.

Some said it was his look. Pre was so fluid, so poetic, with that flowing mop of hair. And he had the broadest, deepest chest imaginable, set on slender legs that were all muscle and never stopped churning.

Also, most runners are introverts, but Pre was an obvious, joyous extrovert. It was never simply running for him. He was always putting on a show, always conscious of the spotlight.

Sometimes I thought the secret to Pre’s appeal was his passion. He didn’t care if he died crossing the finish line, so long as he crossed first. No matter what University of Oregon coach [and Nike cofounder] Bill Bowerman told him, no matter what his body told him, Pre refused to slow down, ease off. He pushed himself to the brink and beyond. This was often a counterproductive strategy, and sometimes it was plainly stupid, and occasionally it was suicidal. But it was always uplifting for the crowd. No matter the sport—no matter the human endeavor, really—total effort will win people’s hearts.

Of course, all Oregonians loved Pre because he was “ours.” He was born in our midst, raised in our rainy forests, and we’d cheered him since he was a pup. We’d watched him break the national 2-mile record as an 18-year-old, and we were with him, step-by-step, through each glorious NCAA championship. Every Oregonian felt emotionally invested in his career.

And at Nike, of course, we were preparing to put our money where our emotions were. We understood that Pre couldn’t switch shoes right before the Trials. He was used to his Adidas. But in time, we were certain, he’d be a Nike athlete, and perhaps the paradigmatic Nike athlete.

With these thoughts in mind, walking down Agate Street toward Hayward Field, I wasn’t surprised to find the place shaking, rocking, trembling with cheers—the Coliseum in Rome could not have been louder when the gladiators and lions were turned loose. We found our seats just in time to see Pre doing his warmups. Every move he made caused a new ripple of excitement. Every time he jogged down one side of the oval, or up the other, the fans along his route stood and went wild. Half of them were wearing T-shirts that read: LEGEND.

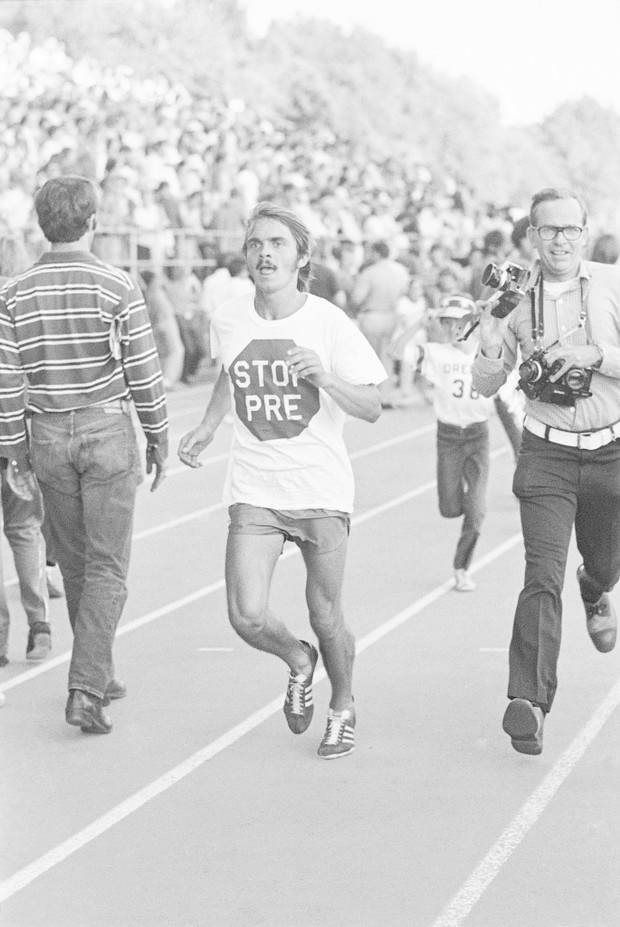

All of a sudden we heard a chorus of deep, guttural boos. Gerry Lindgren, arguably the world’s best distance runner at the time, appeared on the track—wearing a T-shirt that read: STOP PRE. Lindgren had beaten Pre when he was a senior and Pre a freshman, and he wanted everyone, especially Pre, to remember. But when Pre saw Lindgren, and saw the shirt, he just shook his head. And grinned. No pressure. Only more incentive.

The runners took their marks. An unearthly silence fell. Then, bang. The starting gun sounded like a Napoleon cannon.

Pre took the lead right away. Young tucked in right behind him. In no time they pulled well ahead of the field and it became a two-man affair. (Lindgren was far behind, a nonfactor.) Each man’s strategy was clear. Young meant to stay with Pre until the final lap, then use his superior sprint to go by and win. Pre, meanwhile, intended to set such a fast pace at the outset that by the time they got to that final lap, Young’s legs would be gone.

For 11 laps they ran a half stride apart. With the crowd now roaring, frothing, shrieking, the two men entered the final lap. It felt like a boxing match. It felt like a joust. It felt like a bullfight, and we were down to that moment of truth—death hanging in the air. Pre reached down, found another level—we saw him do it. He opened up a yard lead, then two, then five. We saw Young grimacing and we knew that he could not, would not, catch Pre. I told myself, Don’t forget this. Do not forget. I told myself there was much to be learned from such a display of passion, whether you were running a Mile or a company.

As they crossed the tape we all looked up at the clock and saw that both men had broken the American record. Pre had broken it by a shade more. But he wasn’t done. He spotted someone waving a STOP PRE T-shirt and he went over and snatched it and whipped it in circles above his head, like a scalp. What followed was one of the greatest ovations I’ve ever heard, and I’ve spent my life in stadiums.

I’d never witnessed anything quite like that race. And yet I didn’t just witness it. I took part in it. Days later I felt sore in my hams and quads. This, I decided, this is what sports are, what they can do. Like books, sports give people a sense of having lived other lives, of taking part in other people’s victories. And defeats. When sports are at their best, the spirit of the fan merges with the spirit of the athlete, and in that convergence, in that transference, is the oneness that the mystics talk about.

Walking back down Agate Street I knew that race was part of me, would forever be part of me, and I vowed it would also be part of Nike. In our coming battles, with [Japanese supplier] Onitsuka, with whomever, we’d be like Pre. We’d compete as if our lives depended on it.

Because they did.

Continue reading at: runnersworld.com