What Makes Pre So Special

Heroes like Steve Prefontaine never really die. They live on in our hearts and perform their warrior deeds on the big screens of memory and imagination. They define the excellence to which we aspire. They arouse our spirits. They fire our souls.

By Jeff Johnson

Although Steve Prefontaine continues to be widely remembered, idolized and celebrated 40 years after his fatal car accident on May 30, 1975, few think as highly of him as Jeff Johnson.

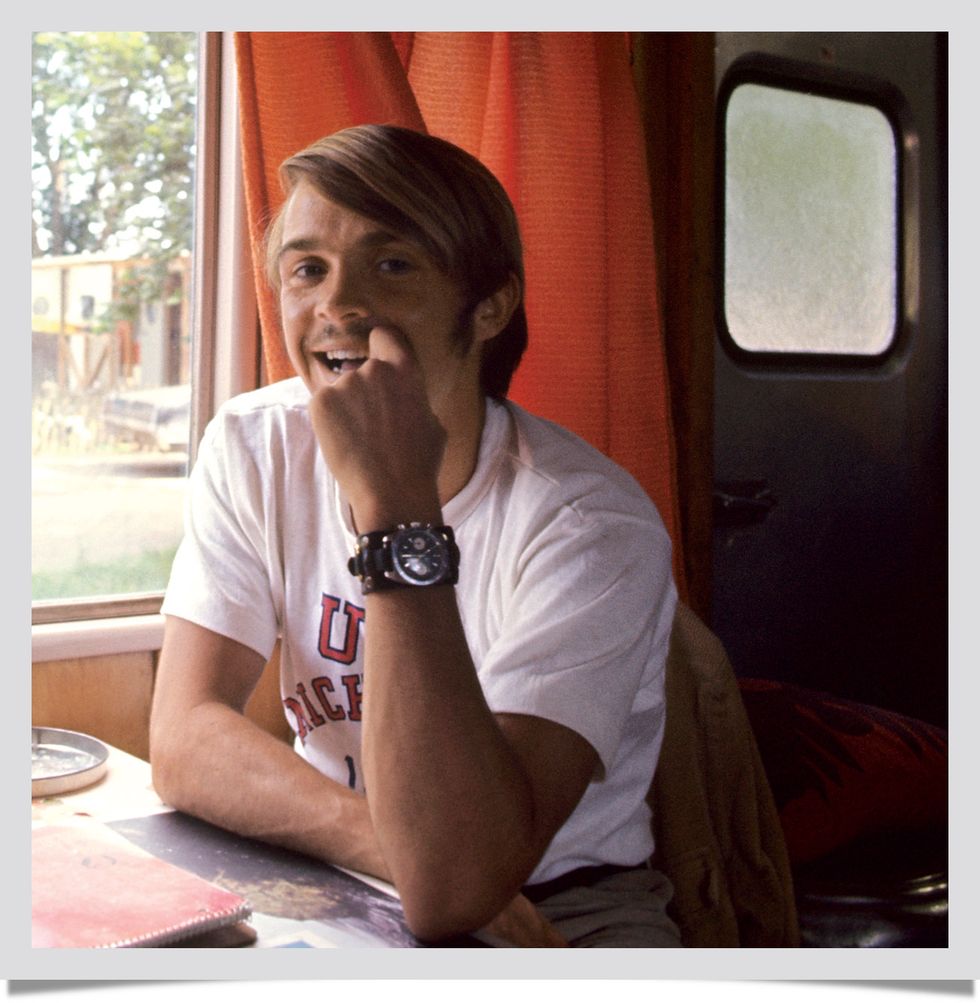

Before he became Nike’s very first paid employee (among other innovations, he came up with the name “Nike”), Johnson was a renowned photographer for "Track & Field News", where he first came into contact with the high school running prodigy from Coos Bay, Ore. Over the next several years, as Johnson shot some of the most enduring action photos of Prefontaine, and then later worked with him at a fledgling running shoe company that featured waffle-iron outsoles, Johnson became a huge admirer of Pre, and frequently speaks about him to Nike employees, high school track teams and runners of all ages.

“He was an enormous force in the lives of those who saw him,” Johnson says now. “And I wanted to capture a sliver of that experience for young people, because there’s never been anyone like him since.”

The following is a speech about Prefontaine that Johnson has given many times, with permission to reprint.

I want to tell you about a boy. A boy who became a legend among American distance runners. People who never saw him run ask, “What was so special about him? He was just a runner.” Well, I will tell you.

It was the summer of 1969, and I was on the campus of the University of Miami for the National AAU Senior Men’s Track & Field Championships. I was just beginning a career as a photojournalist, and this track meet was one of my first assignments. I wanted to do a good job.

And so, I was preoccupied when I stepped into the elevator. As the doors closed, a small boy squeezed in behind me. From the look of him, he was about 12 years old. I ignored him, but as we began our ascent, I became aware that he was looking me over.

“What event do you do?” he asked.

In that distant summer of 1969, I was 27-years-old, fit and undamaged by time. In that elevator of the athletes’ dormitory, one might reasonably have mistaken me for a competing athlete. The boy obviously had. I told him I wasn’t an athlete. I was a photographer for Track & Field News. Then I went back to ignoring him.

“What’s your name?” he persisted.

I told him.

“I’ve seen your pictures,” he said, then proceeded to recall specific pictures I had taken and his opinions of them. I was really impressed. Who even notices the tiny photographer’s credit alongside a picture in a magazine, much less remembers it? This kid was a real fan.

For a moment, I thought he was going to ask me for my autograph. I didn’t ask him his name.

The next evening I saw this boy again. He was standing on the starting line of the 3-mile run, nearly lost among the shadows of America’s best long-distance runners, a gate-crashing child to be pulled aside by officials at any moment so the race might begin. Or so I thought. Then I noticed the mustard-colored vest clinging damply to his chest, and the single word—Marshfield—arched across the front, and recognition finally dawned.

“My God, that’s Steve Prefontaine.”

Few of us knew Pre in that summer of ’69, but nearly everyone had heard of him—the fiery high school runner from Coos Bay, Ore., who that spring had set the scholastic record of 8:41 for 2 miles and who was already known for his audacious, front-running style. In less than six years he would be gone, but in that brief time Pre would gain a reputation that has already spanned a life greater than his own.

He left us the records: Four consecutive NCAA track titles at 3 miles, a feat never before accomplished; American records at every distance from 2000 to 10,000 meters; five years without a loss to any American at any distance greater than a Mile. At Hayward Field, his home track, in front of his fans, his people, he never lost a race longer than a Mile to anyone, American or foreign. Never.

But it isn’t for the record that Pre is remembered. He is remembered for how he competed. And how he lived.

I didn’t know Pre very well, but I’m not here to tell you what he was like. I’m here to tell you why he affected us so much. But I find I can’t do the one without the other, so I’ll tell you what I do know.

I know that Pre was just an unsophisticated, small-town kid. Bill Bowerman called him ‘Rube’ because he was so direct and upfront with people. When they asked him what he meant to do, he would tell them: he was going to win, of course. The media portrayed Pre as cocky. But Pre merely had a child’s enthusiasm for his own potential, and a fierce confidence born from the consistency of his training. According to his coach, Bill Dellinger, in Pre’s four years at the University of Oregon, he never missed a workout. Not one.

Pre had a child’s look about him, too—the girls thought he was cute—an image which pained him and which he tried to change midway through college by growing his hair long and adopting an outlaw’s mustache. But no one was fooled. Though he became a giant slayer, Pre was still just a boy, and the people of Eugene, Ore., embraced him and made him their own.

Pre had a charisma, a personal magnetism that drew people to him, but in every other way he was just a normal college kid. Dellinger described him as just “someone who didn’t know any better and went out and did whatever he said he was going to do.” To his teammates, Pre was easygoing, “just one of the guys.”

He lived in a trailer and survived on food stamps.

He took his dog to class with him.

He grew his own vegetables.

He started a jogging club, then jogged with the joggers. He went to schools and talked with the kids. He went to the state prison and got involved with their programs; he even worked for an inmate’s parole. He seemed to have limitless energy and a desire to make a difference. He was Oregon’s Man of the Year in 1975. A college kid. An athlete. A runner.

He personally organized a track tour to bring Finnish athletes to compete in Eugene, including Lasse Viren, who had beaten him in the ’72 Olympics. And he publicly criticized the AAU—which was then the national governing body of the sport—specifically for not taking the lead in creating more opportunities for international competitions, and generally for its shabby treatment of American athletes. He spoke out against the status quo and stood up for athletes’ rights when few would. And he took considerable heat for it.

He had a kindness about him, especially with children. A father tells a story of taking his son to a meet to see Pre run. Before the race, the boy went to the warm-up area to get Pre’s autograph. When he came back, he told his dad, “Pre wouldn’t sign.”

“Well,” said the father, “Pre is getting ready to race. Ask him later.” After the race, the boy tried again. This time Pre signed. Recognizing the boy from before, Pre asked him, “What are you doing for the next few minutes? Come warm down with me.” As the father tells it, that warm-down jog with Pre changed his son’s life.

He was intensely loyal to his teammates. In 1971, Pre won the conference cross country title with Oregon finishing second. The school was going to send Pre, but not the team, to the NCAA Cross Country Championships in Knoxville. But Pre said he wouldn’t go without his team. So they sent the team. Pre won, leading Oregon to its first-ever NCAA Cross Country team title.

He was loyal to his fans as well. One fall day in 1974, Pre was in Eugene training for a 5000 that he would soon run in Europe. To sharpen, he had planned to run a fast track Mile, and though it was just a workout, no one in Eugene ever missed a chance to see Pre run. One thousand people showed up that day, which was also “field-burning day” in the Willamette Valley, the one day each year when the farmers burned the stubble left in their fields after the harvest. The smoke was so thick you could barely see across the track; it was no day to even be outdoors, much less training. But there were those thousand people. For them, Pre ran his workout Mile in 3:58.3 and coughed blood at the end. And then, his lungs gravely wounded, he found a bullhorn and thanked the people for their support.

Continue reading at: podiumrunner.com

Steve Prefontaine BBTM bio

CREDIT: Nike / Holly Andres